Whale shark gatherings in Gulf shed light on worldâs largest fish

You never forget your first whale shark sighting.

Suddeny there’s a massive 40-foot fish meandering around at the surface, moving so slowly you could swim up and touch it.

Yet, as awe-inspiring as a whale shark sighting can be, there’s still a lot we don’t know about them.

“It’s kind of crazy to think of the world’s largest fish — it’s like a school bus swimming in the ocean — It’s kind of hard to imagine that we don’t know where it goes,” said Jacob Levenson, a marine biologist working for the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, part of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

That’s not all they don’t know. It’s unclear at this point whether these sharks stay in the Gulf of Mexico year-round or migrate up the Atlantic Coast, or even around the world. They don’t know where whale sharks give birth, or how deep they will go.

“They’re a huge mystery, and that’s why I get so drawn into them,” Levenson said.

But Levenson and colleagues at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the University of Southern Mississippi are getting a chance to learn more about these mysterious gentle giants in the Gulf of Mexico this year, thanks to an unusual number of whale shark sightings close to shore, off the Florida Panhandle beach towns like Destin.

Whale sharks normally inhabit deeper waters, over the continental shelf and beyond, but for whatever reason, this year, several of them have strayed closer to shore. Whale sharks are sharks, fish, not whales. They breathe water through their gills, but filter feed by sucking massive volumes of water into their mouths and eating the tiny fish, fish eggs, or crustaceans.

NOAA researcher Eric Hoffmayer, who led the tagging efforts, said the team was able to tag 10 sharks so far, mostly thanks to fishermen or other boaters who reported whale shark sightings to the research team.

“Without their help, maybe two or three animals probably we would have tagged,” Hoffmayer said. “But with their help we were able to get access to 10 animals.”

BOEM is funding the research study to track whale shark populations in the northern Gulf to get a better understanding of whale shark behavior in the Gulf and how human activity might be impacting the species.

Hoffmayer said one of the major aggregation sites for whale sharks in the Gulf, called Ewing Bank, about 60 miles south of Pascagoula, Miss., is close to major shipping lanes, which could be a concern for the animals, listed as endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Whale sharks can be found in tropical and subtropical waters all across the globe, but the Gulf of Mexico seems to be a significant habitat, with two recurring aggregation spots. There are only about 12 of these locations in the world that we know about.

These aggregations can feature dozens or even hundreds of whale sharks converging in a single location to feed, most likely following spawns of tuna or other fish.

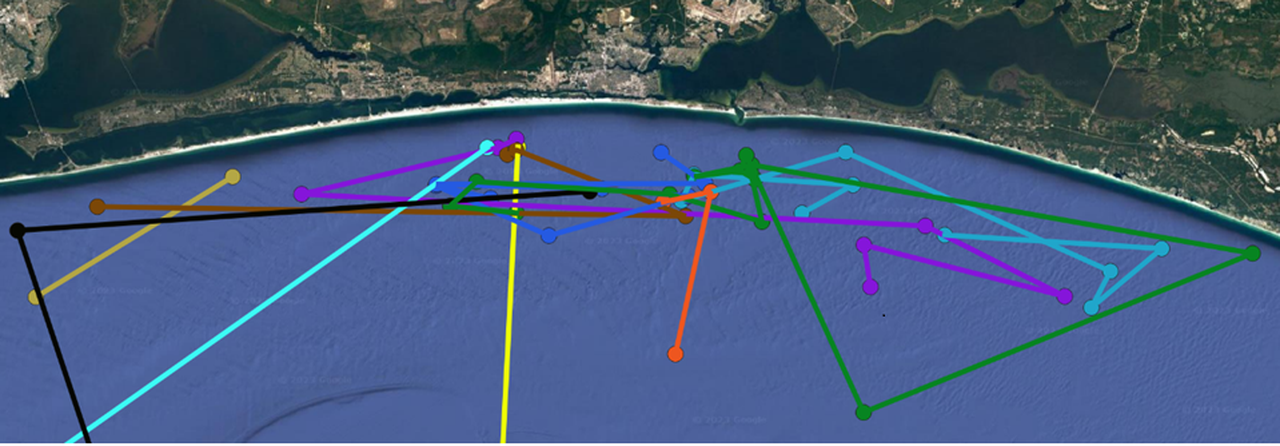

A map of whale shark tracking data off the Florida Panhandle for the summer 2023. Each color represents a different shark, and the trackers transmit a signal every time the shark surfaces.NOAA

Levenson said these aggregations are usually all immature animals and mostly males.

“I think of it as like a frat party kind of thing,” Levenson said.

“Although that sounds way too active. This is a like a bunch of school buses were just kind of driving five miles an hour. They get together in these big aggregations at about 11 or 12 places around the world, one of which is the northern Gulf of Mexico.”

The largest reported aggregation in the Gulf occurred in 2009, when aerial surveys counted approximately 420 whale sharks north of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

Where did the aggregations go?

The original plan was for the researchers to cruise through the Ewing Bank aggregation spot in early July around a full moon.

That’s usually a good recipe for success, Hoffmayer said, but this year the team came up empty. A couple of weeks later, the researchers began getting tips of whale sharks spotted in closer to shore, and arranged to set out from places like Destin or Fort Walton Beach to tag the sharks.

“This was a great opportunity to easily get out there and get some tags out and start collecting data on the movements,” Hoffmayer said.

Researchers believe the whales are following the fish eggs they feed on into shallower waters, perhaps because of variation in surface temperature or ocean currents. They’re documenting the conditions as part of them project to shed some insight on what may be happening to draw the sharks closer to shore, and perhaps away from the places they usually feed like Ewing Bank.

Hoffmayer said whale sharks have been observed coming close to the Panhandle before, most recently in 2009.

“In 2009, we probably had 60 or so sightings of whale sharks I’d say less than 10 miles from the beach from about Pensacola to Panama City,” Hoffmayer said. “And we didn’t quite know what was going on.”

Researchers with NOAA and the University of Southern Mississippi have tagged 10 whale sharks and counting in August 2023.Carlton Ward Jr / Wildpath

This year, they’ve tagged 10 animals successfully, and had a handful of other sightings where the shark disappeared before the researchers could get there.

Hoffmayer and the team at USM haven’t had the funding to tag whale sharks every year. He said before this year’s project, there hasn’t been funding for whale shark tagging in the northern Gulf since 2015.

How do you tag a whale shark?

Once the researchers have a good idea of where the fish will be, they motor out to the location and try to find it. If the shark is located and in good spirits, the researchers begin tagging and documenting the animal.

First the researchers hop into the water with snorkel gear and cameras to photograph the animals on their left side, and sometimes their right.

Whale shark spot patterns are unique to each animal, like a human fingerprint. The researchers will add the photos to an international database so that if the same animal is spotted elsewhere, it can be logged and provide information on how widely these sharks travel.

Hoffmayer said all 10 sharks tagged this year appear to be new entries in the database, meaning they had not been previously recorded for study.

The researchers record the sex and approximate size of the animal. They’ll usually also take a tissue sample that can be used for genetic analysis.

Then, the researchers will attach one of three types of tags to the shark, all providing different information.

The satellite tracker tags are attached to the sharks’ fin.

These satellite tags send the latitude and longitude of the animal when it surfaces, giving clues to the geographic range of the shark for hopefully up to a year, though the tags often break off before then.

The satellite tags can only go down to about 2,000 feet underwater, but the whale sharks have no trouble diving deeper than that, Levenson said. When a shark dives too deep for the tag, it breaks off by design.

The researchers said that in contrast to whales or sea turtles, which have to surface to breathe, whale sharks can stay underwater indefinitely, so they don’t get as many data points.

“Probably half the animals haven’t reported in a couple of days,” Hoffmayer said. “So my guess is that they’re traveling, they’re moving, and so when they decided to come back to the surface, we’ll get some good locations.”

There’s another kind of tag that researchers hope to deploy this year, which closely monitors the whale shark’s movements for roughly a 24-hour period, including their heading, movements, depth, speed, down to how many tail beats the shark makes.

“It’s basically a Fitbit for sharks,” Levenson said.

“We can create a computer visualization of a day in the life of a whale shark, and we can do that with shipping data and boat data and understand what is their risk of vessel collisions?”

These tags only last about 24 hours before detaching.

The longest-lasting are acoustic transmitter tags, which broadcast a signal into the water. Those signals are logged by receivers all over the world’s oceans to track a shark’s long-term movements. Those tags can last up to 10 years, but can also be rubbed off if the animal brushes against the seafloor or other structure.

The whole tagging process only takes a few minutes.

“Typically it takes us two passes and we can collect all the information we need,” Hoffmayer said. “And then if the animal hangs around, then we just collect more video.”

If you see a whale shark…

Levenson said that if boat captains or anyone roaming the Gulf sees a whale shark, they can report it here.

Otherwise, he says to take in the sights, but to do so responsibly, without harassing the animal.

“If I could tell somebody three things, it would be No. 1, dude, they’re awesome if you have a chance to see one,” Levenson said. “No. 2, be careful operating [boats] around them because there are a lot of propeller scars on them because they hang out so close to the surface. And No. 3, absolutely let us know.”